Emily Dickinson, Cognitive Sciences + Sociology Minor, Class of ’20

Brief Summary: The second-largest city in America, Los Angeles possesses an extensive network of literary institutions, including its public library system, bookstores, and various nonprofits. Hailing from California herself, Dickinson reflects on her personal experiences of these organizations/entities as she describes them. In this paper, conceptions of the public humanities, place, capitalism, and city development come together in the discussion of the city’s literary infrastructure.

“We get that money is tight, we understand that there is a hierarchy of needs, and that the French Market or a Mark Twain plaque are not hospital beds and classroom size. But [libraries] are still a significant part of our social reality, the only thing left on the high street that doesn’t want either your soul or your wallet.”

-Zadie Smith

I. Introduction

Literature is often seen as solitary and highly individual. Many people engage with books on their own. English papers are written for the professor rather than for the class. The notion of public humanities is puzzling at times. We forget that there are public aspects to literature. The structure of upper level English courses is typically one that keeps separate class discussions between peers that are led by teachers, and individually written papers for the professor. There is rarely a sharing of information between students in the work that they produce. My Literary Houston class is the first class I’ve taken that has focused on the idea of public engagement with the humanities, and in particular literature. Literary infrastructure, in this paper, is concerned with public engagement with literature in many forms. Most often this takes form through public library programs, literary-focused non-profit organizations, local independent bookstores, educational writing resources, and much more. Literary infrastructure is very important to the development of a city culture that is supportive of artists and writers. It also provides opportunities for engagement with literature in public and social settings.

I have a personal interest in the city of Los Angeles as a site for literary infrastructure because I grew up in a small suburb of northeast Los Angeles called La Canada. La Canada is home to NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and just next door to the larger city of Pasadena, home of the Rose Bowl and the annual New Year’s Rose Parade. My personal experience with Los Angeles’ literary infrastructure has barely scratched the surface, but I am excited to explore and attend events in the future.

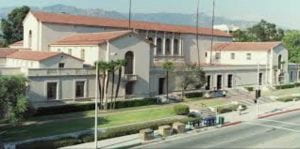

My most significant exposure to the literary infrastructure of LA has been through the library system. Public libraries provide a welcoming environment and easy access to free knowledge. The LA Central Library has a domed entryway with detailed paintings and mosaics that filled me with awe the first time I saw it on a field trip in elementary school. The library, built in 1922, is a historical landmark in the city and is the third largest library in the United States.

The LA Public Library system has 72 branches throughout LA county. Each library hosts its own community events, open mics, readings, and movie showings. They also often provide free citizenship, literacy, and job interview preparation classes (Los Angeles Public Library). Libraries are one of the last public spaces that are completely free of charge to enter (Smith 2012). One of my favorite authors, Zadie Smith, wrote an essay in defense of her local public library and an adjacent independent bookstore in London that was facing closure and replacement with apartment buildings. After reading her essay, I was surprised when I failed to think of other public spaces that are free to enter and free of capitalist pressures to consume, buy, or sell. There aren’t many places left where you are allowed to loiter and linger, and libraries, although limited in their hours, provide a space to just be and to learn. Libraries are an incredible resource for communities, providing free access to knowledge, as well as shelter from the heat or cold.

My main library growing up was the Pasadena Central Library, which is a large building with a grand main hall with high ceilings. It has a children’s wing where I spent many afternoons after school because it was across the street from my mother’s work. I went to storybook readings as a kid and was thrilled to participate in a summer Harry Potter Camp. Both the Pasadena Central Library and the Los Angeles Central Library have incredible architecture with high ceilings and beautiful wooden shelves. I love libraries. I feel that there are fewer and fewer truly free public spaces, where there is no cost of entry.

My love for the Pasadena Central Library was renewed this past summer, when I spent up to six hours a day, Monday through Friday, studying for the MCAT in the library. People watching while sitting out in the courtyard next to the coffee shop during lunch, baking in the LA heat, was one of the few highlights of my day. I liked how there were so many different people in the library, and reaching a tacit understanding with other library regulars was a quietly collective experience that I really enjoyed. My experience with the library and its role in fostering a sense of community and comfort is just one example of how literary infrastructures support and enrich people’s lives.

II. Los Angeles: Place and History

I have chosen to look at the literary infrastructure in Los Angeles because it has several remarkable similarities to Houston. Both cities are large urban sprawls with pockets of dense populations. Both cities are car cities with horrible traffic and complex freeway or highway systems. Both cities have large and vibrant Latinx communities. The racial and ethnic demographic breakdown in Los Angeles is 49% Latinx, 29% White, 11% Asian, 9% black, and 2% more than one race (LACity.org), and the city has a poverty rate of 20% (welfareinfo.org). Houston has 49.3% white, 17% black, and 7.8% Asian, and 2.1% other, and 37.6% Latinx (Houston.org), with a poverty rate of 21% (welfareinfo.org). Both cities have high rates of homelessness, housing segregation, and rising levels of gentrification1. Despite many similarities, one key difference between Houston and Los Angeles is how the cities market themselves. Los Angeles is home to Hollywood, attracting actors, screen writers, and artists. Los Angeles has become a place to go if you want to enter into the entertainment industry, and sometimes it feels like everyone in LA is a screenwriter or at the very least working on “something.” The city has many writers and artists, making it a prime location for gaining more information about literary infrastructures and support for the public humanities.

In order to understand literary infrastructure in a particular place, such as the city of Los Angeles, it is important to have a historical context for how cities develop and to have a critical understanding of place for the seemingly obvious reason that the literary infrastructures exist in a particular place with a particular history and context. According to Cresswell (2004), places have a purpose and a connection to humans and the human production of meaning. Places create worlds of meaning and experience, and spaces become places when they have been attributed meaning. Many locations become cities for reasons that seem logical such as centrality, harbors, transportation crossroads, or water supply. Interestingly, Los Angeles lacked all of those natural factors that tend to correlate with growth. Los Angeles was competing with San Diego and San Francisco for resources to develop and grow, but thanks to the political maneuvering of a few key investors and the combined interests of several industries, the city of Los Angeles received large federal grants to construct a port, creating the largest artificial harbor of its time (Logan and Molotch).

One of the defining characteristics of a city is the density and proximity of people living in its space. As people make a place out of a space, they become part of a collective and develop connections based on the occupancy of proximal space. Place is a type of commodity, but a special one. Places can be sentimental and feel like home. Places provide access to school, friends, work, shops, etc. It connects any one person to a range of organizations, physical resources, and other commodities. There is a collective interest among individuals that have “bought” into an area: people that share a common fate during natural disasters, infrastructure changes (highways, parks, factories, toxic dumps), etc.

Logan and Molotch argue that the commodity-like features of places lead to city development through what they call growth machines. Growth machines are characterized by “value free” development, the idea that free markets alone should decide land use. Through collective action, pro-growth associations create alliances and compete to attract federal grants, resources, businesses, museums, colleges, sport franchises, convention centers, prisons etc. to an area. Logan and Molotch argue that growth machines evolve from small groups of local power brokers into a complex matrix of social and public institutions “that deflect public consciousness from the potential negative social and environmental consequences of urban development” (112). Pro-growth associations are able to leverage their wealth to create infrastructure. Like all infrastructure, literary infrastructure requires investment and needs to be built up over time. Power is central to the ability to create, and minority groups who lack hegemonic power due to institutionalized racism often struggle to participate in and develop their own literary infrastructures.

III. Literary Infrastructures in Los Angeles

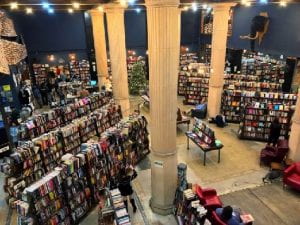

Independent bookstores are a key part of literary infrastructures. One bookstore that I feel stands out in Los Angeles is the Last Bookstore, located in the heart of downtown on Spring Street. The Last Bookstore hosts lots of readings, live music events, as well as conversations or interviews with writers, comedians, and thinkers. The bookstore sells records, art, and books, and tucked away upstairs is an extensive library of donated used books that are sold at low prices. They host monthly book clubs for multiple genres, including mystery, feminist lit, queer lit, true crime, and afro-futurist lit. They have also served as a space for a zine convention. Below is a picture taken of the downstairs layout.

The Last Bookstore has strong ties to the visual arts community in Los Angeles, with a permanent gallery space with rotating art exhibits.

The Last Bookstore has made itself an attraction spot for tourists through interesting and innovative permanent art displays. Commonly seen on Instagram pages, the store is adorned by book arches, book windows, and long streams of book pages hanging from the ceiling that swirl playfully throughout the store. The bookstore is big with high, open ceilings, but it still has a cozy feel with soft, well-worn couches. I have fond memories of browsing through their books and reading little passages out loud with my best friend from high school. Reading together has shifted my experience with books beyond a solitary interaction with a text into a shared meaningful moment. Local independent bookstores create places out of spaces for books, poems, and ideas to be shared with others. Through book clubs, conversations with writers, and other events, the Last Bookstore creates a community of people that are connected by a mutual recognition and appreciation for literature.

Nonprofits represent another key component of literary infrastructures, and Los Angeles is home to many such groups attempting to increase access to the literary arts.2 Below, I introduce many key actors in the Los Angeles literary nonprofit world:

826LA is a chapter of a national organization that provides free programming for kids ages 6 to 18 to inspire writing skills. They also do after school tutoring, field trips, workshops, and help kids publish some of their work. 826’s national headquarters is located in San Francisco, and they have two locations in Los Angeles. From their 2018 annual report, 826 has become the largest youth writing support organization in the US with 8 chapters across the country. They have a 1.7 million dollar annual budget (although I am unsure if this is the national organization budget, or if individual chapters have their own budget as well). Their funding source percentile breakdown is 35% corporate, 35% foundations, 14% chapter fees, 11% individual, 2% earned income, 1% government funded. All of their programs are free or pay what you want. Their website also features a shout-out from Michelle Obama, which speaks to their level of prestige and national clout.

PenAmerica is a national organization that is based in NY and several other major cities. PenAmerica holds several annual pop-up events in Los Angeles, including LA LitFest. In order to fundraise, they host LA LitFest Gala, which is similar to the Inprint gala in Houston, but likely on a larger and pricier scale. The organization is very well funded. One indication of their scale of wealth is that they rent out the ballroom of the four seasons hotel in Beverly Hills for the LA LitFest Gala. Pen America does community outreach and advocacy against banned books in schools and prisons, as well as offers grants, awards, and emergency writers funds.

Los Angeles Poet Society (LAPS), started in 2009, hosts open mics, workshops, and two yearly poetry contests. They host 75 events a year including Venice Beach soapbox events allowing writers to read their writings on a literal soapbox on the boardwalk, as well as Writer Wednesdays at a local coffee shop. LAPS works with the LA Art Walk and displays writer’s works in written form in a gallery during the monthly LA Art Walk. Based on the mission of the organization, LAPS is dedicated to serving as an anchor for LA’s literary community, promoting other local literary events and organizing events to highlight members of the organization who can join for free. LAPS is currently involved in the #shedoes social movement, advocating for homeless women and using poetry to raise awareness. Their website is full of opportunities to submit written work, and the organization partners with California Poets in Schools and 100Thousand Poets for Change. It is also branching out into Creative Aging programs with their new Senior Advocacy branch. The sponsors page on their website doesn’t give much budget information, and while I assume that they are reasonably well funded, they do not seem to have an operating budget that is nearly as high as national organizations like 826 or PenAmerica.

Minority Specific Non-Profits:

The University of Guadalajara Foundation hosts an annual Spanish book festival called LeaLA. The University of Guadalajara Foundation is a non-profit that works with a system of universities to provide educational opportunities in science technology, writing, and maintenance of culture through art. This nonprofit is not specific to literature. One interesting feature is that it does not have just one main center or location. The partnerships that the foundation has with other universities makes it an example of an organization with a nonprofit structure beyond a traditional community center model, where all events take place at one location. One of the benefits of organizations that look beyond community centers is that they are able to resist the effects of gentrification by adapting to changes in community location. In doing so, they help to ensure that community literacy, history, and creativity are not eroded away with time: instead, these aspects of culture and life can be preserved and nourished independent of a centralized physical place. Avenue50 Studios is a nonprofit that focuses on Chicano/a culture and visual art in northeast Los Angeles. They host a monthly poetry open mic called La Palabra. In addition, they also host LA poets and writers in readings throughout the year. Avenue50 also has an art gallery and works with local artists. They are funded by other foundations including the LA county Arts Council, Cal Humanities, and The Department of Cultural Affairs, among many others.

The Free Black Women’s Library L.A. is a feminist pop-up book library. They have an ongoing book swap in their library for books written by black women. They also host community-led workshops, panel discussions, and other literary events. Based on a GoFundMe page linked on the website, the budget of the organization is relatively small: a recent fundraising goal was just 800 dollars. They also have an Amazon wish list that donors can use to help add books to the library.

IV. Conclusion

The Los Angeles literary infrastructure is broad and ranging. Only a few of its components have been discussed here, but there are many more. Los Angeles has pretty successfully marketed itself as a place for the arts, in large part because of the ways that pieces of the literary infrastructure work together. The Los Angeles Poets Society advertises a host of literary events on their website, for example. The Last Bookstore, several independent art galleries, and the Los Angeles Poets Society all work with the Los Angeles Art Walk to open up spaces to display art, written word pieces, and music. While there is some sense of literary ecosystem, I think that more work can be done to connect minority-specific nonprofits with larger and more established nonprofits to create a more integrated literary infrastructure.

In speaking with Tony Diaz, the director of the Houston nonprofit Nuestra Palabra, our class learned about some of the particular challenges of the nonprofit model. Difficulty in securing grants beyond operating budgets and the sacrifice of individual career choices in favor of nonprofit management have been challenges for Nuestra Palabra and other Houston nonprofits like Talento Bilingue. While it is unknown the extent to which these same issues plague the Los Angeles nonprofits described here, they have the potential to face similar issues. One thing I thought was interesting about the minority nonprofits reviewed here is that they were more likely to have pop-up events. Due to gentrification, several arts-based community centers have been pushed out, and important community places have been lost.

Researching literary infrastructures in Los Angeles for this paper and reflecting on my past experiences has really broadened my knowledge of what is out there. I am encouraged to continue exploring the numerous events and resources that are available to me in a city like Los Angeles. Literary infrastructure provides opportunities to make places out of spaces and foster strong communities of writers and literature readers. It is more than just a building or a space to read: it is a place to connect and experience with others.

Works Cited

Cresswell, Tim. Place: A Short Introduction. Blackwell Pub., 2004.

“Houston Demographics – Race/Ethnicity.” Houston.org, www.houston.org/houston-data/demographics-raceethnicity.

“Los Angeles Demographics.” LACity.org, www.planning.lacity.org/resources/demographics.

Los Angeles Public Library. City of Los Angeles, 2020, https://www.lapl.org/.

Molotch, Harvey, and John Logan. “The City as a Growth Machine: Toward a Political Economy of Place.” Cities and Society, 1987, pp. 15–27.

“Poverty in Houston, Texas.” Welfare Info, 2017, https://www.welfareinfo.org/poverty-rate/texas/houston.

“Poverty in Los Angeles, California.” Welfare Info, 2017, https://www.welfareinfo.org/poverty-rate/california/los-angeles.

Smith, Zadie. “North Western London Blues.” NYBooks, NYBooks, 2012, www.nybooks.com/daily/2012/06/02/north-west-london-blues/.

[1] For more information on homelesssness and housing in Houston and Los Angeles, see:

- Homelessness in Houston: https://www.searchhomeless.org/about/homelessness-in-houston/

- Homelessness in Los Angeles: https://losangelesmission.org/the-state-of-homelessness/,

- Housing Segregation: https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2018/national/segregation-us-cities/

- Gentrification in Houston: https://kinder.rice.edu/urbanedge/2020/01/08/neighborhoods-texas%E2%80%99-biggest-cities-are-gentrifying-and-it%E2%80%99s-happening-fastest-houston

- Gentrification in Los Angeles: https://www.governing.com/gov-data/los-angeles-gentrification-maps-demographic-data.html

[2] For more information on the Los Angeles literary infrastructures discussed in the paper, see:

- LA County Library website – https://www.lapl.org/branches/central-library

- Pasadena Public Library website: https://www.cityofpasadena.net/library/

- Last Bookstore website: http://lastbookstorela.com/

- PENAmerica website: https://pen.org/

- LA poet Society website: https://www.lapoetsociety.org/

- 826LA website: 826La.org for national org info: http://www.826national.org/

- University of Guadalajara Foundation website: http://udgusa.org/en/homepageen/

- Avenue50 studios website: https://www.avenue50studio.org/

- Free Black Women’s Library website: http://www.thefreeblackwomenslibla.com/